The beginning of air rights can be traced to the 1797 Slate vs. David court decision that involved two stolen barrels of herrings buried 15 feet under the accused’s yard. The court determined that anything above or below the soil belonged to the possessor of the soil. This legal concept of air rights was based in the Latin phrase Cuius est solum, eius est usque ad caelum et ad inferos, “For whoever owns the soil, it is theirs up to Heaven and down to Hell.” In the early 1900s, after the invention of airplanes and increase of air traffic, the space above the soil was amended to “within the range of actual occupation.”

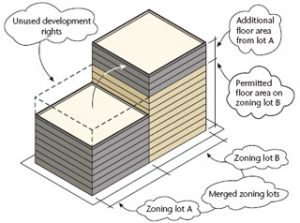

New York City air rights, i.e. Transferable Development Rights, or TDRs – originated with the 1961 revamping of the city’s zoning laws which allow for the transfer of unused development rights to another development site. The transfer of these air rights allows buildings to become taller and bigger than the city zoning code allows. In essence, if a building adjacent to a construction site is lower than neighborhood zoning laws allow, the developer can acquire the building’s unused air space, add it to his or her project, and erect a taller building. Since the upper floors of a building fetch higher prices, developers consider height to be a prime asset.

The standard unit for development rights in New York City is the floor area ratio (FAR). Floor Area Ratio, or FAR, is the principal bulk regulation controlling the scale of buildings. FAR is the ratio of total building floor area allowed to the area of its host zoning lot. A higher FAR generally allows larger buildings and a lower FAR allows smaller buildings.

The standard unit for development rights in New York City is the floor area ratio (FAR). Floor Area Ratio, or FAR, is the principal bulk regulation controlling the scale of buildings. FAR is the ratio of total building floor area allowed to the area of its host zoning lot. A higher FAR generally allows larger buildings and a lower FAR allows smaller buildings.

The Zoning Resolution defines the floor area ratio as: “… the total floor area on a zoning lot, divided by the lot area of that zoning lot. (For example, a building containing 20,000 square feet of floor area on a zoning lot of 10,000 square feet has a floor area ratio of 2.0.)” Densities for various land uses are described by the Zoning Resolution in terms of the FAR for that use in that zone.

The city allows property owners to transfer development rights in three ways:

- Zoning lot mergers permit an owner to transfer development rights, as of right, to adjacent properties on the same block. Zoning lot mergers are the primary way that development rights are transferred in the city.

- Landmark transfers, which require a special permit, allow the owners of landmarks to transfer unused development rights to adjacent parcels on the same block, across the street, or, if the landmark is on a corner, to any lot on another corner that touches the same intersection.

- Special transfer programs have been created by the Department of City Planning as part of larger planning projects, such as the Special West Chelsea District (the High Line), the Hudson Yards District, and the Theater Subdistrict. Some of these programs—like West Chelsea and Hudson Yards—have linked additional density or TDR transfers to the development of affordable housing.

“Vandana Ranjan has been representing me as my agent to sell my property. During the time we have worked together I have developed a respect for her abilities and self motivation and, more importantly, a trust for her integrity and dedication. I was particularly pleased that she would initiate appropriate ideas and actions to sell my property and stay on top of the selling process; often taking the initiative to identify and obtain needed information and documents. I would unreservedly recommend her services to anyone, as I already have to my own daughter.” — Mort D.

Sources: